1. eTox - omics datasets¶

Editor’s summary

The authors of this recipe provide an overview of the advantages of so-called knowledge resource indexes.

They identify 1) coverage report, and 2) entity mappings as useful applications enabled by knowledge resource indexes.

1.1. Motivation and Aim¶

The description of the metadata as well as the characterization of the actual content of a dataset often rely on short free-text excerpts. As an example, we can consider the names of the columns of a table (e.g. “laboratory tests”) or the different values of the cells belonging to a specific table column (e.g. “cholesterol”, “blood sugar”, “liver function”, etc.). Often such free-text excerpts are not rigorously characterized inside and across datasets, thus leading to situations in which it is difficult to unambiguously describe the semantics of each excerpt due to polysemy (i.e. several meanings can be associated to the same excerpt) and synonymy (i.e. a specific meaning can be expressed by more than one excerpt).

In this regard, the possibility to describe both the structure (i.e. metadata) and content of a dataset by relying on the concepts formalized by widely-adopted knowledge resources (i.e. ontologies, thesauri, etc.) plays a key role in substantially improving the level of FAIRness of the same data: the identification of the concepts that better describe each piece of information included in a dataset is usually referred to as entity linking. The use of standardized, shared, consistent identifiers to unambiguously characterize the semantics of data fosters Interoperability and Reusability: indeed, the fact that distinct datasets rely on the same, shared set of concepts to describe (part of) their content makes their integration significantly easier, thus opening up novel possibilities for cross-fertilization. Also the Findability and Accessibility of information significantly benefit from the availability of descriptions of datasets based on standard vocabularies: information from distinct datasets can be seamlessly indexed and searched and data consumers, both humans and machines, can easily interpret, validate and summarize their content.

Given a dataset, this FAIRification Recipe focuses on (semi-)automated approaches and best practices to:

support the selection of the knowledge resources (i.e. ontologies, thesauri, etc.) that provide higher semantic coverage with respect to the description of the structure (i.e. metadata) and content of the dataset

enable the selection from these knowledge resources, of (sets of) concepts useful to describe the structure and content of the dataset

1.2. Why you need to decide between different Knowledge Resources¶

As a general consideration, given a dataset, the selection of the knowledge resources useful to describe its structure and content should be driven by the following general principles:

the selection of a specific knowledge resource among a set of alternatives should be driven by: (i) higher semantic coverage with respect to the description of the dataset under consideration; (ii) better formalization of key facets of the data to describe with respect to the implementation of future data integration and indexing activities; (iii) higher level of integration and availability of mappings from the chosen knowledge resources to other complementary ones

the reuse and combination of existing, widespread knowledge resources should be privileged as much as possible

when (part of) the semantics of the dataset can’t be formalized by any existing knowledge resources, the extension of an existing knowledge resources should be preferred over the creation of a new one, to cover such semantic gap

1.3. What are Knowledge Resource Indexes?¶

Knowledge resource indexes represent core tools to enable data normalization and integration through concept mapping, thus fostering the reuse of existing knowledge resources. Knowledge resource indexes are repositories where several types of knowledge resources (e.g. ontologies, thesauri, etc.), usually describing distinct facets of a knowledge domain, are stored. Such indexes provide users with specific mechanisms to identify inside the set of indexed knowledge resources, the most relevant concepts useful to formally characterize the semantics of a piece of knowledge that is usually represented by a text excerpt. In particular, given a text excerpt (i.e. “neoplasia”), knowledge resource indexes select and rank concepts useful to characterize its semantics by relying on string matching strategies: the set of concepts that are described by labels (i.e. names or longer descriptions) that better match the text excerpt provided as input are retrieved. For instance, given the input text excerpt “neoplasia”, the concept with identifier MC_0000002 lexicalized by means of the label “Neoplasia”, belonging to the Histopathology ontology is retrieved. In this FAIRification Recipe, we will rely on the EBI Ontology Lookup Service (OLS), a knowledge resource index that at the time of writing, stores the most recent versions of 236 widespread biomedical ontologies. OLS provides an open REST API that supports the retrieval of the most relevant concepts useful to describe a text excerpt provided as input.

Hereinafter this FAIRification Recipe, by relying on the OLS API, given an input dataset, presents into detail an automated ontology coverage evaluation strategy. Such strategy aims at: (i) identifying the knowledge resources that better describe the structure (i.e. metadata) and content of the dataset under consideration, in terms of semantic coverage; (ii) gathering the most relevant concepts useful to characterize each piece of knowledge that belongs to the input dataset (i.e. each text excerpt that describes a specific aspect of the input dataset). In particular, basic linguistic analyses are performed on both the descriptive text excerpts provided as input to the OLS API and the labels of the corresponding related concepts that are retrieved by the same API. By pre-processing each input text excerpt we intend to perform basic query expansion procedures with the aim of increasing the recall of relevant concepts when querying the OLS knowledge resource indexer. By analyzing the labels of the list of matching concepts retrieved by the OLS API, we intend to refine such concept list by relying on rules and heuristics based on linguistic analyses. When we deal with the evaluation of the semantic coverage of knowledge resources, it is not uncommon that the indexers we have at our disposal (e.g. the OLS) do not include all the knowledge resources we would like to consider as potential sources of useful concepts. To mitigate this issue, we rely on OntoIndex, a knowledge resource indexer based on Elasticsearch and developed by the Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM), Barcelona. The current version of OntoIndex supports the import, indexing and search for concepts that belong to ontologies formalized by means of the Ontology Web Language (OWL) or the Open Biological and Biomedical Ontology (OBO) format, the latter widely adopted to describe biomedical knowledge resources.

1.4. Using Knowledge Resource Indexes¶

The exploitation of the concepts formalized by widely-adopted knowledge resources (i.e. ontologies, thesauri, etc.) to semantically describe the structure (i.e. metadata) and content of a dataset is a key aspect to foster the FAIRness of the same data. With this regard, here we present an approach whose ultimate objective is easing and automating the choice and usage of a consistent and informed set of knowledge resources to describe a dataset under consideration. In particular, the proposed strategy automatically evaluates the suitability of a set of knowledge resources (i.e. ontologies, thesauri, etc.) with respect to the semantic characterization of a list of terms that occur in an input dataset (i.e. the presence inside the considered knowledge resources, of concepts that properly describe the terms belonging to the input list).

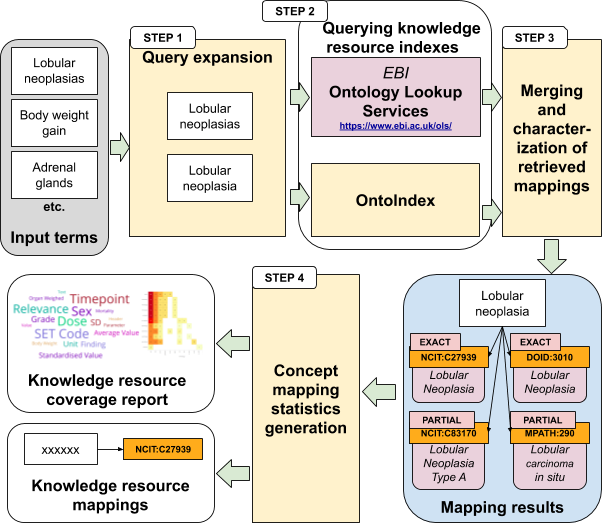

The input of our approach is represented by a list of terms (i.e. short free-text excerpts, see Fig. 1.9) that are used to describe a varied set of aspects of a dataset under analysis (e.g. the names of the columns of the tables of the dataset - i.e. cell headers). By considering the knowledge resources stored in as index (namely the OLS, eventually complemented by OntoIndex) we intend to generate as final outputs:

a knowledge resource coverage report: that provides statistics about the semantic coverage of the knowledge resources stored in the index. The coverage is evaluated in terms of number of input terms described by the concepts formalized in a specific knowledge resource. In particular, we evaluate the semantic coverage by considering exclusively exact matches or partial matches of terms to concepts (see below for a detailed description exact and partial matches)

a list of knowledge resource mappings: for each input term we generate an easy-to-review list of exact matches and partial matches of terms to knowledge resource concepts

The knowledge resource coverage report provides useful insights to select the set of knowledge resources that better support the semantic characterization of the dataset under analysis. Moreover, the list of knowledge resource mappings enables users to explore term specific mappings to concepts in order to obtain finer-grained information on the quality of the automatically generated mappings as well as to support activities of manual revision and validation of the proposed mappings.

The sequential steps that compose the proposed approach are (see Fig. 1.9):

Query expansion: we analyze the text of each input term. In case it includes plural nouns or adjectives we generate an alternative term substituting plural with singular words (the term “neoplasias” generates the alternative term “neoplasia”). We also consider the presence of punctuation in the input term, generating an alternative term without punctuation. All the text analyses exploited during the query expansion step are performed by relying on the Stanford CoreNLP tools. This strategy is motivated by the fact that some knowledge resource indexes like the OLS substantially change their results if we consider linguistic variations of the query string, for instance with respect to the singular and plural forms of nouns and adjectives. For instance, at the time of writing, when we query the OLS, all the top-10 results (i.e. matching ontological concepts) we get for the input term “neoplasm” are different from the top-10 results we can retrieve if we use the plural of the same term, “neoplasms”.

Querying knowledge resource indexes: by considering each input term as well as each related alternative term obtained by the term expansion, we query (a set of) knowledge resource indexes. In particular, in Fig. 1.10 the following knowledge resource indexes are considered: the OLS index and OntoIndex. The latter is a knowledge resource indexer developed by the Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM), Barcelona. It is exploited to complement the OLS when we need to search for concept matches against knowledge resources that are not contemplated by the OLS.

Merging and characterization of retrieved mappings: for each input term, eventually complemented with alternative terms by query expansion, each knowledge resource index retrieves a set of matching concepts. We merge all the concepts retrieved by the knowledge resource indexes by querying such index by considering both the input term and its alternative terms. The merging strategy is mainly useful to avoid duplicate concepts. From the set of merged matching concepts that describe an input term we derive two non-intersecting subsets: concepts with exact match and concepts with partial match (see below for a detailed description exact and partial matches).

Concept mapping statistics generation: this final step takes care of the generation of both knowledge resource coverage report and the list of knowledge resource mappings, previously described in detail.

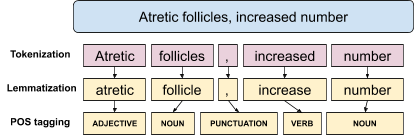

To conclude the description of this FAIRification recipe, we explain the approach we use to identify two subsets of concepts referred to as exact matches and partial matches, starting from the whole set of concepts matching a specific input term. We analyze each term as well as each label associated with the retrieved matching concepts by means of the Stanford CoreNLP tools: we process each one of these texts by performing tokenization, lemmatization and PartOfSpeech tagging. Fig. 1.10 shows an example of textual analysis of the term “Atretic follicles, increased number”.

Given an input term and a label of a related matching concept, we consider the following two types of matches:

Exact match: when the set of lemmas belonging to the input term and the set of lemmas belonging to the concept label are equal. We exclude from this comparison lemmas identified as punctuation, numbers, determiners and conjunctions. We consider as negated exact matches (a particular type of exact matches) scenarios in which the set of lemmas of the input term and and the set of lemmas of the concept label differ by the addition of the negation words no, not and without

Partial match: when the set of lemmas belonging to the input term and the set of lemmas belonging to the concept label: (i) in their intersection include at least one noun and (ii) all the lemmas that belong only to the concept label (i.e. are not present in the input term), if any, are not nouns

These heuristics will be refined and extended iteratively by exploring term to concept matching results. When given an input term, there are several synonyms (i.e. alternative labels) of a matching concepts that represent exact or partial matches, we classify the term to concept match as exact or partial by means of the following rules:

if one or more exact matches are present, the term to concept match is described as an exact match and one of the labels (randomly chosen) of the matching concept that generated the exact match, is considered

if no exact matches are present, the term to concept match is described as a partial match. If there is more than one label of the matching concept that generated a partial match we consider the concept labels that has the higher number of shared lemmas with the original term

Fig. 1.9 Overview of the automatic ontology coverage evaluation strategy.¶

Fig. 1.10 Example of textual analyses of terms / concept labels.¶

1.5. References¶

References

1.6. Authors¶

Authors

Name |

ORCID |

Affiliation |

Type |

ELIXIR Node |

Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

IMIM |

Writing - Original Draft |