1. Interlinking data from different sources¶

1.1. Main Objectives¶

The FAIR principles, under Interoperability state that:

I3. (Meta)data include qualified references to other (meta)data

This is understood as providing metadata with machine readable cross-references when possible.

The main goals of this recipe are:

To understand where the need arises for mapping between data identifiers.

How to represent equivalences for use by others.

Know what services are available to support data interoperability.

This recipe assumes that you are already familiar with identifiers and the minting of identifiers.

For more details on identifiers, see the Unique, persistent identifiers recipe.

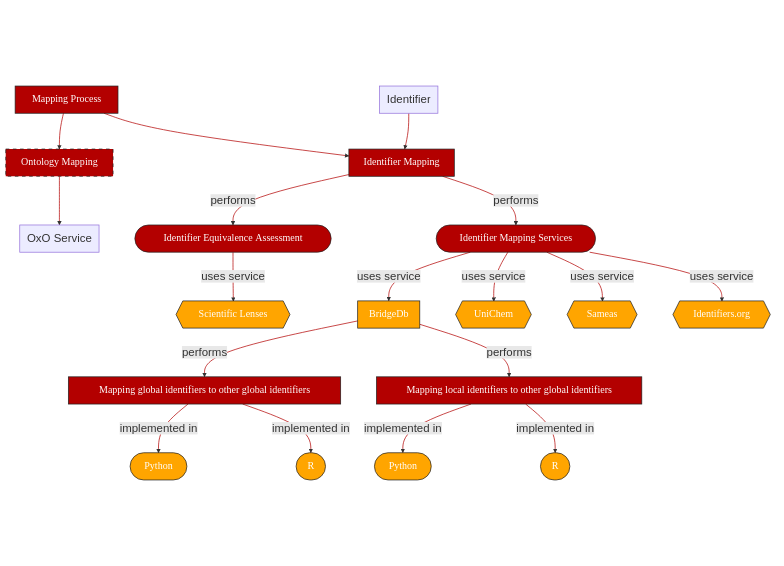

1.2. Graphical Overview¶

This recipe will cover the topics highlighted in orange:

Fig. 1.2 Overview of key aspects in Identifier Mapping¶

1.3. Capability & Maturity Table¶

Capability |

Initial Maturity Level |

Final Maturity Level |

|---|---|---|

Interoperability |

minimal |

repeatable |

Identifier mapping |

repeatable |

1.4. Table of Data Standards¶

Data Formats |

Terminologies |

Models |

|---|---|---|

1.5. Mappings¶

Before diving into identifier mapping, it is important to understand the possible types of mappings that can be performed between entities. While initially we might think of mapping as simply linking identical entities in different databases/formats, sometimes related entities might also be of interest. When these mappings might only be interesting depending on the context in which data is being used, we run into a situation that has been described as “scientific lenses” (see 1). These lenses allow us to dynamically select which mappings to consider relevant and which to ignore. For example allowing or disallowing mappings between stereoisomers or between genes and proteins.

Examples of types of mappings are:

Content mapping: where we are mapping the actual entities by using techniques such as BLAST in biological sequences or comparing InChI identifiers for chemical compounds.

Ontology mapping: this can either be:

As a direct 1-to-1 mapping between equivalent terms in different ontologies.

As a complex m-to-m mapping between terms in different ontologies taking into account their hierarchical structure, see {footcite}.

wang_concept_2010.

Identifier mapping: The focus of this recipe. This can either be:

Mapping between differently formed identifiers that resolve to the same entity. (e.g. the same gene with different identifiers under HGNC and Ensembl).

Mapping between identical local identifiers with different namespaces (e.g. PDB where there exist regional mirrors of the database so accesion/local identifier is the same but namespace is different).

Mapping between entities that are related enough to be usefully connected (e.g. linking information on proteins, genes, RNA and reporter sequences for these).

Mapping between databases containing different information about the same entity (e.g. links between the protein sequence database UniProt and the protein 3D structure database PDB).

1.6. Identifier Mappings¶

Note

“Identifiers are used to tag, identify, find and retrieve entities which are part of a collection or a resource maintained by some organization. “

To satisfy the Findability criteria F1, organisations must create identifiers for the concepts within their database. This generates locally unique identifiers which can in turn be transformed into globally unique identifiers using namespaces for which the database organisation are the authority.

Databases often contain data that exists in, or is closely related to, the content of other databases. For example, the genome database Ensembl contains data about genes that are related to entries in databases such as HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (https://www.genenames.org/) or NCBI Gene; or a database about drugs, e.g. DrugBank, often contains details of the chemical substance that forms the drug which are also contained in chemical databases such as ChEBI or PubChem. This results in a large number of unique identifiers notionally for the same concept. This large number of identifiers for the same concept prevents interoperability of the data, since additional knowledge is needed to know which identifiers represent the same concept from different databases. However, the databases often contain cross-reference links to other databases to represent these equivalences.

The need for each database to mint their own identifier is a result of each taking a different perspective on the concept. For example, a chemical database will distinguish between different salt forms of the chemical whereas a drug database may not contain this differentiation. These differences in perspective are driven by the goal of the databse in terms of the data that they store. The interlinking of these data items can affect the reuse of the data in applications. As such, the declaration of cross-references should be done in a way that allows others to understand the nature of the equivalence declared, and therefore determine if it is appropriate for their use (see 1 for more details).

While the minting of identifiers is often done in isolation of other organisations, there are instances of databases who reuse identifiers from a well known community database. For example, the Human Protein Atlas database reuses Ensembl identifiers for their data records. In these cases there is no need to map between the data instances in the two databases, the data is already connected through the common identifier. However, this means that the Human Protein Atlas must ensure that their definition of the concept is exactly aligned with the Ensembl identifier for all application uses.

1.7. Identifier Equivalences¶

Identifier equivalences can come about in several ways and capture different forms of relationship as presented in Mappings.

For example, a database may declare that their record is the same as an entry in another because they share the same name, or they may declare it based on a common representation (gene sequence or InChI).

To support reuse of the data, the provenance of the cross-references needs to be made explicit.

Depending on the nature of the data, there are different ways that equivalences can be computed.

Some elements to take into consideration are:

a mapping predicate taken from a well known ontology, e.g.

owl:sameAsorskos:narrower.the evidence behind the equivalence claims, e.g. a similarity score or the property on which the equivalence is based such as InChI Key for chemicals.

audit trail information, i.e. who, what, when, e.g.

agent X using mapping tool Y on YYYY-MM-DD. PROV-O ontology could be used to support such statements.

1.8. Exchanging Identifier Mappings¶

There are several file format for exchanging identifier equivalences. We will discuss the most widely used formats and demonstrate them with a sample of data derived from ChEMBL which provides cross-reference equivalences for two records in the ChEMBL database to UniProt proteins.

1.8.1. Using Text File¶

The simplest way to exchange equivalences is in a simple text file, which could be structured as a tab-separated-value (TSV) file. Such a file usually consists of two columns, one per dataset, and each row represents an equivalence declaration. The interpretation is that the two identifiers on the same row are equivalent in some way. These files tend to carry little to no metadata about the mappings, i.e. the mechanism by which the mapping was derived is not given, nor are details of the version of the datasets that were linked.

The following example shows the mapping equivalences between ChEMBL target components (proteins) and UniProt proteins.

ChEMBL_Target_Component UniProt

CHEMBL_TC_4803 A0ZX81

CHEMBL_TC_2584 A1ZA98

1.8.2. Using Simple Standard for Sharing Ontology Mappings (SSSOM) formatted text files¶

The OBOFoundry Simple Standard for Sharing Ontology Mappings (SSSOM) is a newly emerging standard for exchanging mapping information with minimal metadata, although the minimal model is extensible. It consists of a tab-separated-value file (TSV) with each row representing a mapping. The columns in the file have been defined by the community (latest version) and provide the mapping together with its provenance. At present, four columns are required (subject_id, predicate_id, object_id, match_type) with optional columns to provide more provenance to support the mapping, e.g. licensing information, author information, creation method. The use of CURIEs within the TSV is strongly encouraged.

The following TSV shows our example data as a mapping file using the minimal columns (correct as of November 2020). The information provided is less than the minimal VoID model above.

subject_id predicate_id object_id match_type

chembl:CHEMBL_TC_4803 skos:exactMatch uniprot:A0ZX81 sio:database-cross-reference

chembl:CHEMBL_TC_2584 skos:exactMatch uniprot:A1ZA98 sio:database-cross-reference

1.8.3. Using Vocabulary of Interlinked Datasets Linkset Files¶

The Vocabulary of Interlinked Datasets (VoID) provides an ontology of terms for describing RDF datasets. These descriptions include basic information about the dataset, e.g. its name, description, license, etc, but also introduces a mechanism for exchanging data instance mappings called linksets.

A linkset contains the identifier mappings together with either the metadata at the top of the file or a link to a VoID file describing the data source. The Open PHACTS project defined a usage profile for use within the life sciences community Open PHACTS Dataset Descriptions which was later refined by the W3C Health Care and Life Sciences Community Group (W3C HCLS Linksets).

The following example shows a VoID Linkset in turtle notation with the minimum metadata given in the header. The metadata block links to the ChEMBL 17 RDF description and the UniProt March 2015 release. The linkPredicate tells us that the link is an exact match, i.e. the linked instances can be deemed equivalent for most applications, and the linksetJustification property states that the link is declared as a Database Cross Reference assertion, rather than being computed based on an equivalent protein sequence. These properties allow consuming applications to make more informed choices about their reuse of the data.

@prefix bdb: <http://vocabularies.bridgedb.org/ops#> .

@prefix chembl: <http://rdf.ebi.ac.uk/resource/chembl/> .

@prefix chembl_target_cmpt: <http://rdf.ebi.ac.uk/resource/chembl/targetcomponent/> .

@prefix sio: <https://semanticscience.org/resource/> .

@prefix skos: <http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#> .

@prefix uniprot: <http://purl.uniprot.org/uniprot/> .

@prefix void: <http://rdfs.org/ns/void#> .

@prefix xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#> .

:chembl17-uniprot-exactMatch-linkset a void:Linkset ;

void:subjectsTarget :chembl17-rdf ;

void:objectsTarget <http://purl.uniprot.org/void#UniProtDataset_2015_03> ;

void:linkPredicate skos:exactMatch ;

bdb:linksetJustification sio:database-cross-reference

void:triples "6367"^^xsd:integer .

chembl_target_cmpt:CHEMBL_TC_4803 skos:exactMatch uniprot:A0ZX81 .

chembl_target_cmpt:CHEMBL_TC_2584 skos:exactMatch uniprot:A1ZA98 .

...

1.8.4. A couple of observations¶

SSSOM is an emerging community standard that is still not finalised. While the basic metadata model has less information than the VoID file, there are additional properties for providing more detail. Properties that related to the set of mappings can can be included as a comment block at the start of the TSV.

The VoID Linkset approach for exchanging mappings separates the metadata from the data mappings. This eliminates duplication of metadata. However, as currently defined, the VoID Linksets can only be used for RDF data. The above has shown that the two formats can represent the same information. Both VoID and SSSOM can be used to provide very rich metadata for exchanging data.

1.9. Identifier Mapping services¶

Identifier mapping services are databases that contain lists of identifiers, often from different databases, that are known to be equivalent. These are consumed from original data sources and third parties in one of the formats provided above.

The common functionality offered by these services is to return a set of equivalent identifiers for a given identifier. That is, you can ask these services for all identifiers that are equivalent to your identifier. The services will vary in the response depending on their coverage of data sources and whether they decide to compute the transitive closure of the identifiers. That is, if data source A declares that A:id1 is equivalent to B:acc32, and data source C declares that C:67cb2865-781f-4450-a99c-e9b33bf4d5b5 is equivalent to B:acc32, should a lookup for equivalent identifiers for A:id1 return C:67cb2865-781f-4450-a99c-e9b33bf4d5b5 since A:id1 <=> B:acc32 and B:acc32 <=> C:67cb2865-781f-4450-a99c-e9b33bf4d5b5.

The following is an incomplete list of identifier mapping services.

-

BridgeDb 3 is a framework for identifier mapping within the life sciences which covers genes, proteins, genetic variants, metabolites, and metabolic reactions. It is provided as a web service, a standalone application that can be installed locally, a Java library or an R Package.

It permits users to lookup equivalent database identifiers for a given database identifier within a specified organism. The following

curlcommand to the REST API retrieves the equivalent identifiers for the EntrezGene (now known as NCBI Gene)Lidentifier1234for theHumangene CCR5 as a TSV file.curl -X GET "https://webservice.bridgedb.org/Human/xrefs/L/1234" -H "accept: */*"

-

UniChem 2 is a specialised identifier mapping service for chemical structures. For a chemical structure – specified as an identifier, InChI, or InChI Key – it will equivalent structures found in the EMBL-EBI chemistry resources.

The following

curlcommand retrieves the equivalent database identifiers for the ChEMBL identifierCHEMBL12DIAZEPAM and returns the result as a JSON object.curl -X GET "https://www.ebi.ac.uk/unichem/rest/src_compound_id/CHEMBL12/1" -H "accept: */*"

For more information including the available methods, see the UniChem REST documentation.

-

sameas.org is a general purpose service that will return a set of equivalent URLs for a given URL. The equivalences are based on an incomplete set of

owl:sameAsstatements contained in data available on the web.The following

curlcommand retrieves the equivalent URLs for EBI RDF Platform representation of ChEMBL DIAZEPAM as a JSON object.curl -iLH "Accept: application/json" "http://sameas.org/?uri=http://rdf.ebi.ac.uk/resource/chembl/molecule/CHEMBL12"

Note that the coverage of http://sameas.org within the life sciences is very small.

1.10. Conclusion¶

In this recipe, we have given an overview of the need to map between globally unique and persistent identifiers from different data sources where they cover the same concept, i.e. FAIR principle I3. We have covered:

The idea of data identifier equivalence;

How to publish and exchange data identifier equivalences;

Data identifier mapping services which can be queried to find equivalences for a given identifier.

Data identifier equivalences increase the interoperability between data sources since it allows data about an individual to be integrated together. As a minimum, you should aim to link your dataset’s persistant data identifiers to one major dataset within the community. The ELIXIR Core Data Resources provide a useful list of major datasets within the life sciences.

1.11. References¶

References

- 1(1,2)

Colin Batchelor, Christian Y A Brenninkmeijer, Christine Chichester, Mark Davies, Daniela Digles, Ian Dunlop, Chris T Evelo, Anna Gaulton, Carole Goble, Alasdair J G Gray, Paul Groth, Lee Harland, Karen Karapetyan, Antonis Loizou, John P Overington, Steve Pettifer, Jon Steele, Robert Stevens, Valery Tkachenko, Andra Waagmeester, Antony Williams, and Egon L Willighagen. Scientific Lenses to Support Multiple Views over Linked Chemistry Data. In The Semantic Web – ISWC 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 16. 2014. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11964-9_7.

- 2

Jon Chambers, Mark Davies, Anna Gaulton, Anne Hersey, Sameer Velankar, Robert Petryszak, Janna Hastings, Louisa Bellis, Shaun McGlinchey, and John P. Overington. UniChem: a unified chemical structure cross-referencing and identifier tracking system. Journal of Cheminformatics, 5(1):3, January 2013. doi:10.1186/1758-2946-5-3.

- 3

Martijn P. van Iersel, Alexander R. Pico, Thomas Kelder, Jianjiong Gao, Isaac Ho, Kristina Hanspers, Bruce R. Conklin, and Chris T. Evelo. The BridgeDb framework: standardized access to gene, protein and metabolite identifier mapping services. BMC Bioinformatics, 11(1):5, January 2010. URL: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-5 (visited on 2021-02-05), doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-5.

1.12. Authors¶

Authors

Name |

ORCID |

Affiliation |

Type |

ELIXIR Node |

Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Heriot Watt University |

Writing - Original Draft |

||||

Maastricht University |

Writing - Original Draft |

||||

Maastricht University |

Writing - Original Draft |

||||

Maastricht University |

Writing - Review & Editing |

||||

University of Oxford |

Writing - Review & Editing |