6. IMI EUBOPEN FAIR High-Content Screening data deposition¶

6.1. Abstract¶

This datatype-specific recipe for bio-imaging data, specifically High-Content Screening data for compound libraries, provides:

information on available data and metadata standards, as well as on missing pieces.

recommends domain-specific repositories.

ways to structure your data.

If you run high-content screens to test the effect of compounds on cells and want to make your data FAIR, this recipe is for you.

6.2. Background¶

High-content screening (HCS) is about detecting a phenotypic change in living cells following exposure to a test compound.

HCS typically generates data with a large volume rate (60 GB / hour).

Typically, 384-well plates are imaged regularly in an automated microscope to investigate the time-dependent phenotypic change after treatment with test compound, compared to a placebo treatment.

Thus, hundreds of different compounds might be tested in parallel, and a typical experiment might run for 48 hours, giving rise to high-volume, high-velocity, complex data.

Automated analysis is therefore key to providing interpretable results fast.

6.2.1. Additional reading¶

More Background on the datatype “BioImaging” and associated methods.

6.4. Table of Software and Tools¶

Tool Name |

|---|

6.5. (Meta-)Data standards for images¶

There is not a single data standard for microscopy images.

One of the advanced open community standards is OME-TIFF.

Ideally, your HCS instrument produces an open data format by default, and not a proprietary vendor-specific format. To find out, you can consult the user manual of your instrument, or try to work with tools like “tiffutil” to investigate the produced files.

Possibly, multiple images are combined into one file, e.g. z-stacks, time series, or versions with different resolutions of the same image.

For some use cases this might be beneficial, for others undesired.

Some are optimized for cloud compute, others for local compute.

Transfer and conversion of data sets is typically a challenge because of the high data volume.

You might need to resort to high-speed transfer tooling to transfer data fast enough, such as Aspera, especially when in industrial settings.

(Meta-)Data might be embedded into the file containing the image, e.g. in OME-TIFF format.

This might include “identifiers”, e.g. a URN in OME-TIFF, but also further information, e.g. about the employed excitation/emission filters during the imaging.

In some formats, e.g. OME-XML, this information is held in separate files, linking to other files through their identifiers.

Strict definitions of “data” and “metadata” did not reach community-consensus in the field yet, and can be generally assumed missing.

6.6. (Meta-)Data standard for high-content screening experiments¶

There is not a single specification around a metadata standard for high-content screening experiments.

The most advanced recommendation is REMBI, the “Recommended Metadata for Biological Images” 1 .

REMBI spans different layers of granularity, from study, over samples, to images and even analyzed data. This granularity is not necessarily reflected in the ways available to store information in files.

Strict definitions of “data” vs. “metadata” did not reach community-consensus in the field.

6.7. Repositories for high-content screening data¶

Given the high volume and velocity of HCS data, you might find yourself wanting to deposit your data as soon as possible into a public repository, away from your HCS instrument.

A typical alternative set-up is the availability of large network-connected storage, which is used to store the intermediate data until it is analyzed by automated methods.

A possibility to start is the BioImage Archive, which allows to deposit any files in a submission.

Each submission receives a persistent identifier in the sense of an URL promised to be persistent; individual files do not receive individual identifiers, but are accessible via HTTP-resolvable URLs.

You will need to find your own way to represent your data in BioImage Archive or similar repositories, as no community-agreed standards exist.

An exemplar of a data deposition including information about the assayed compounds and links to raw data, description of the analysis pipeline, and processed images can be retrieved using this BioStudies accession number: S-BIAD145

6.8. Tips for pragmatic Research Data Management in High-Content Screening¶

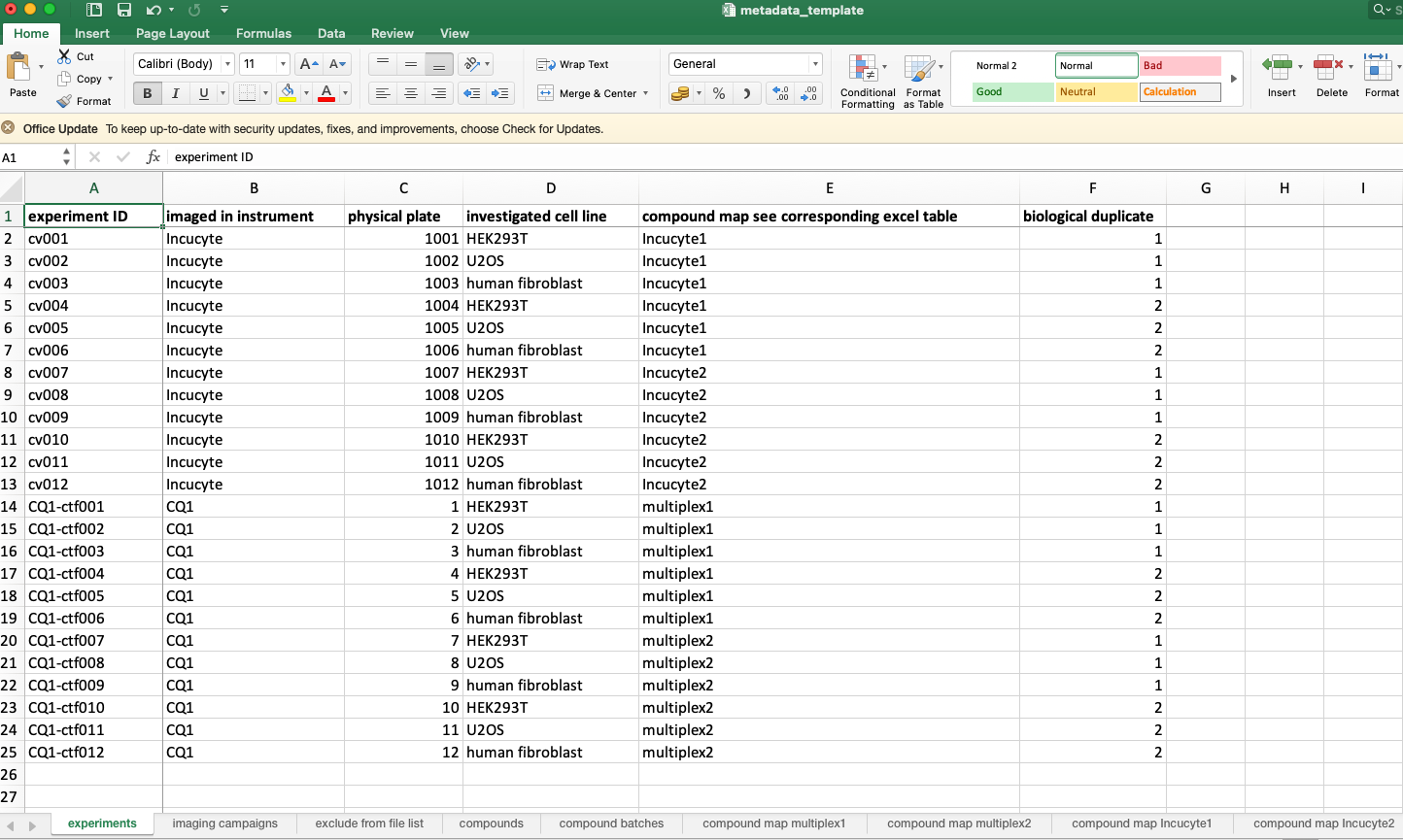

To enable automated compound assessment, the authors of this recipe found it helpful to separate the following entities conceptually: experiments, imaging data acquisitions, compounds, compound batches, compound maps.

Those entities can be described in a database-like Excel file for each of your experiments, and can be easily quality-controlled.

The IT footprint of this solution is minimal, and might be perfectly suited if you do not work in a company performing exclusively HCS experiments.

This should allow you to connect your final results with the underlying “metadata” about the actual experiments.

An exemplar of an implementation is described in the published protocol “High-Content Live-Cell Multiplex Screen for Chemogenomics Compound Annotation based on Nuclear Morphology” (in preparation), with the corresponding Python code available on Zenodo: doi:10.5281/zenodo.6325622

6.9. Step-by-step recipe¶

Download the Python scripts and the metadata template Excel sheet from doi:10.5281/zenodo.6325622. or this GitHub repository

Organize your metadata according to the metadata template sheet.

Fig. 6.5 Overview of the bioimage-excel.¶

Generate file lists with the Python scripts.

python first_python_script.py yourinputfilelist.xlsx

Zip the raw data, and upload the zip files as well as the individual processed images to BioImage Archive.

Run the automated analysis of your data with the Python scripts.

python other_python_script.py other_input_file.extension

Upload your analysis data and the aggregated version to Zenodo.

6.10. Conclusion¶

With this content and the associated python scripts, we highlight path to deposit HCS imaging data the EMBL-EBI BioImage Archive. This therefore improves Findability and Reusability of such data.

6.10.1. What to read next?¶

6.11. References¶

References

- 1

U. Sarkans, W. Chiu, L. Collinson, M. C. Darrow, J. Ellenberg, D. Grunwald, J. K. Hériché, A. Iudin, G. G. Martins, T. Meehan, K. Narayan, A. Patwardhan, M. R. G. Russell, H. R. Saibil, C. Strambio-De-Castillia, J. R. Swedlow, C. Tischer, V. Uhlmann, P. Verkade, M. Barlow, O. Bayraktar, E. Birney, C. Catavitello, C. Cawthorne, S. Wagner-Conrad, E. Duke, P. Paul-Gilloteaux, E. Gustin, M. Harkiolaki, P. Kankaanpää, T. Lemberger, J. McEntyre, J. Moore, A. W. Nicholls, S. Onami, H. Parkinson, M. Parsons, M. Romanchikova, N. Sofroniew, J. Swoger, N. Utz, L. M. Voortman, F. Wong, P. Zhang, G. J. Kleywegt, and A. Brazma. REMBI: Recommended Metadata for Biological Images-enabling reuse of microscopy data in biology. Nat Methods, 18(12):1418–1422, 12 2021.

6.12. Authors¶

Authors

Name |

ORCID |

Affiliation |

Type |

ELIXIR Node |

Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bayer AG |

Writing - Original Draft |

||||

University of Luxembourg |

Writing - Review & Editing |

||||

University of Oxford |

Writing - Review & Editing |